|

Thank you for visiting.

Click here for the Japanese version

My name is Kitao Nakamura, the developer of the PC Engine emulator

Ootake.

In recent years, many re-released retro games—especially

classic arcade titles— have been

published with their pixel aspect

ratios (the shape of each character pixel) either ignored or

determined incorrectly.

As a result, the true quality of these

masterpieces is often not fully conveyed.

In Gradius II, a pixel‑by‑pixel display is exactly the world

the

designers intended. * pixel‑by‑pixel = 1:1 pixel mapping

Gradius II is a masterpiece that has been re-released many

times over the years.

However, in three of the recent

re-releases—Arcade Archives Gradius II, Arcade Classics

Anniversary Collection, and Gradius: Origin Collection—the

default setting stretches the original 320x224 game

image to fill a 4:3 virtual TV screen.

This results in the pixels being vertically stretched by a

factor of 1.07, making the character designs appear unnaturally

tall.

This is clearly incorrect. Anyone who has

actually played the game may notice that the artificial sun in

Stage 1 looks far too thin vertically.

And those who own

the original PCB will immediately see that the square test grid

pattern shown at boot is no longer square under this display

method—it becomes noticeably elongated vertically

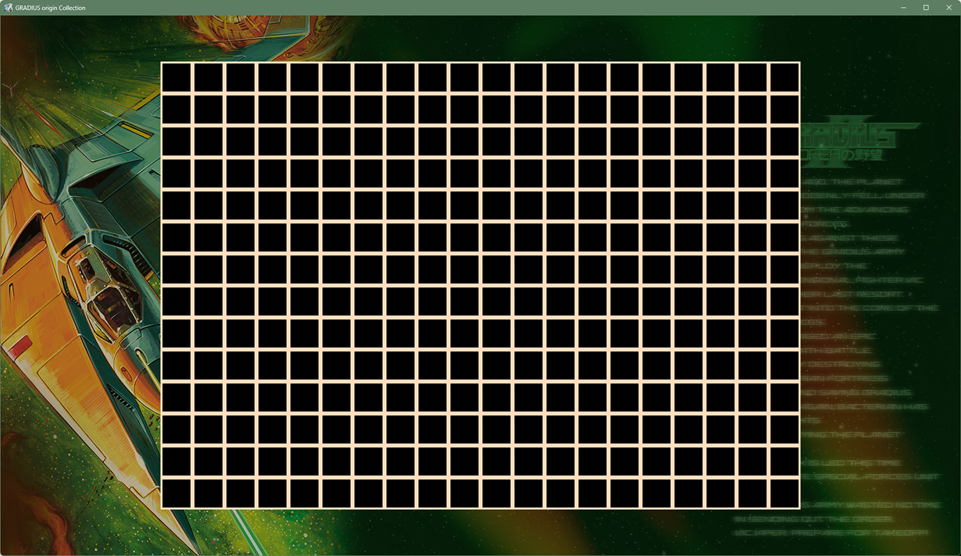

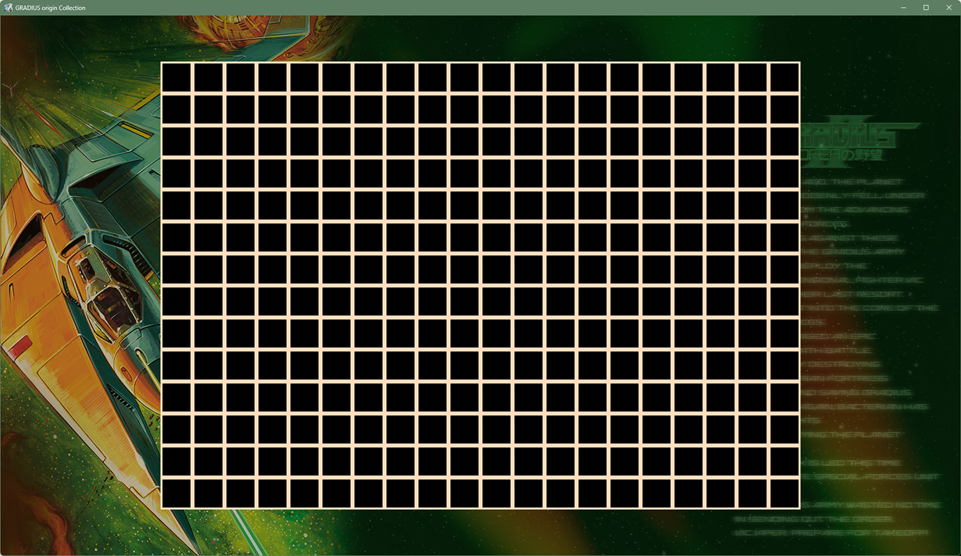

↓The default display in the Origin Collection.

The test grid becomes vertically elongated.

Source:『Gradius: Origin Collection』(©

Konami Digital Entertainment)

↓Display using the Origin Collection’s "Dot by Dot

(pixel‑by‑pixel)" setting.

The test grid now

appears as perfect squares.

Source:『Gradius: Origin Collection』(©

Konami Digital Entertainment)

This white mesh test grid was the key tool arcade staff used to

adjust the pixel aspect ratio on CRT monitors.

By tuning

the display so that this test pattern appeared as perfect

squares, the staff ensured the game looked as natural as

possible—exactly as the developers intended.

In Gradius

II, each black square in the test grid is displayed as 14x14

pixels—perfect squares with the same number of pixels vertically

and horizontally.

This strongly suggests that the

developers intended the CRT to be adjusted so that each

pixel appears as a square pixel.

* On

modern PCs and consoles, this corresponds to a true

pixel‑by‑pixel (1:1) display.

Once the

display is adjusted correctly, the artificial sun in Stage 1 no

longer looks unnaturally thin.

Even that slight roundness

makes a surprisingly big difference in how the game feels—the

sun simply has more visual impact.

Naturally, this also

changes how enjoyable the game feels after playing.

↓The default display in the Origin Collection.

The artificial sun appears vertically stretched.

Source:『Gradius: Origin Collection』(©

Konami Digital Entertainment)

↓Display using the Origin Collection’s "Dot by Dot

(pixel‑by‑pixel)" setting.

The artificial sun

now appears properly round.

Source:『Gradius: Origin

Collection』(© Konami Digital Entertainment)

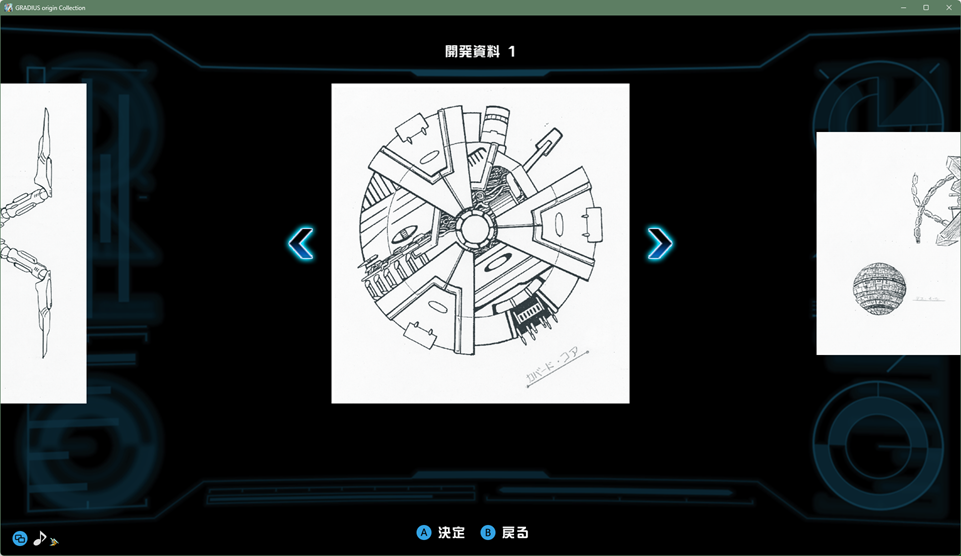

There is another decisive piece of evidence that Gradius II was

meant to be displayed pixel‑by‑pixel.

It lies in Stage

7’s boss, the Covered Core. According to design materials from

the original character artist, the Covered Core was

drawn as a perfect circle.

This clearly

indicates that the intended aspect ratio was one in which

circles appear truly circular.

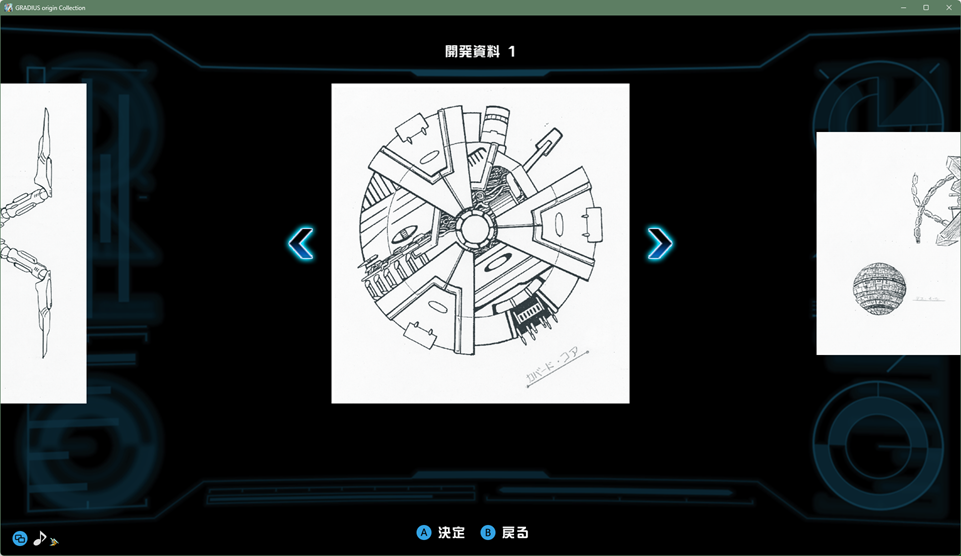

↓Design materials

from the original artist. The rotating cover of the

Stage 7 boss, the Covered Core, is drawn as a perfect circle.

Source:『Gradius: Origin Collection』(©

Konami Digital Entertainment)

↓Display using the Origin Collection’s "Dot by Dot

(pixel‑by‑pixel)" setting.

The cover also

rotates as a perfect circle in‑game.

Source:『Gradius: Origin Collection』(©

Konami Digital Entertainment)

In the three currently available versions of Gradius II, the

Covered Core is slightly horizontally compressed by default,

causing it to appear vertically stretched.

As a result, the

cover no longer rotates as a perfect circle, breaking the

intended visual effect.

Earlier releases had similar

issues due to hardware limitations:

the PC Engine version

(horizontal pixel ratio x1.14), the PlayStation version (x0.80),

and the Sega Saturn version (x0.91) all deviated noticeably from

true square pixels.

Of course, even with incorrect pixel

aspect ratios, the game is still highly enjoyable—it’s a

masterpiece with far more to offer than just visuals.

But

when it comes to truly falling in love with the

experience, I personally feel that an inaccurate pixel

aspect ratio becomes a significant handicap.

One more thing I noticed while capturing images from the

Gradius: Origin Collection was the way certain sound effects

behaved.

In particular, the Ripple Laser in Gradius II

normally has a very satisfying sound, but in this release it

consistently felt unpleasant to my ears. I sincerely hope this

can be improved in a future update.

Another issue was

that lowering the volume below 100 caused the overall sound

pressure to drop significantly.

I personally worked

around this by raising the volume from the default value of 70

up to 100.

That said, the large amount of included materials

and the extensive sound gallery are truly excellent.

|

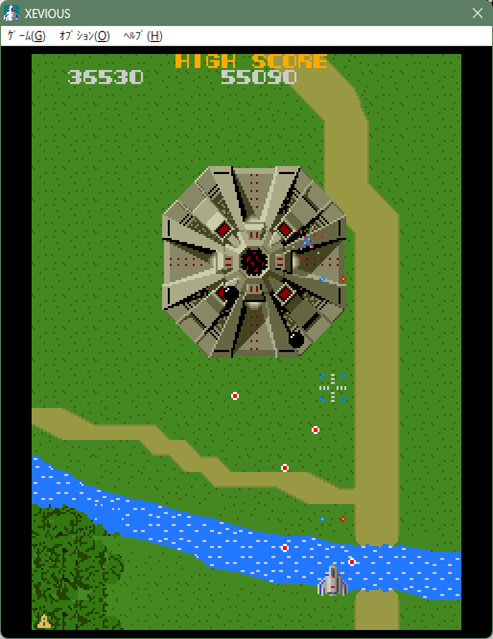

For Andor Genesis in Xevious, the

designer’s intended world is one

built around perfect squares.

Let’s look at another title—Xevious, the classic that

introduced players to its world with its imposing boss

characters.

In the recent Arcade Archives release of

Xevious, the default setting stretches the original

224x288‑pixel game screen to fill a virtual 3:4 vertically

oriented display.

As a result, the pixels are

horizontally compressed to about 0.96x, making the character

designs appear slightly elongated vertically.

The

distortion is small enough that many players may not notice it.

However, longtime Xevious fans will likely spot it the moment

they face Andor Genesis—realizing that it’s not quite the

perfect square it’s supposed to be.

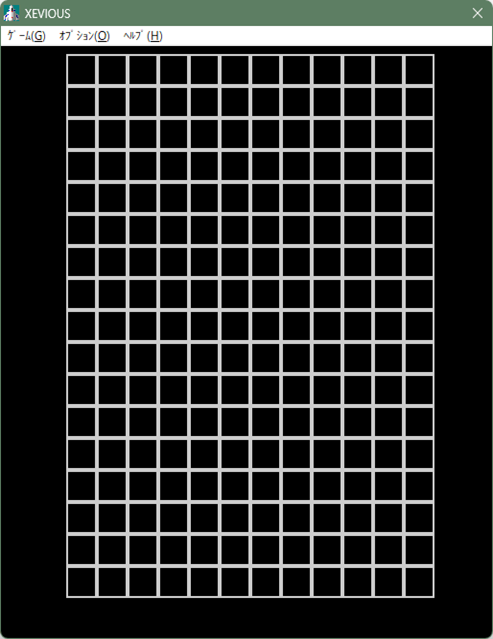

Anyone who owns the

original arcade PCB would also notice that the square test‑grid

pattern (the white mesh shown at boot) no longer appears as true

squares under this display method, but instead becomes slightly

vertically stretched.

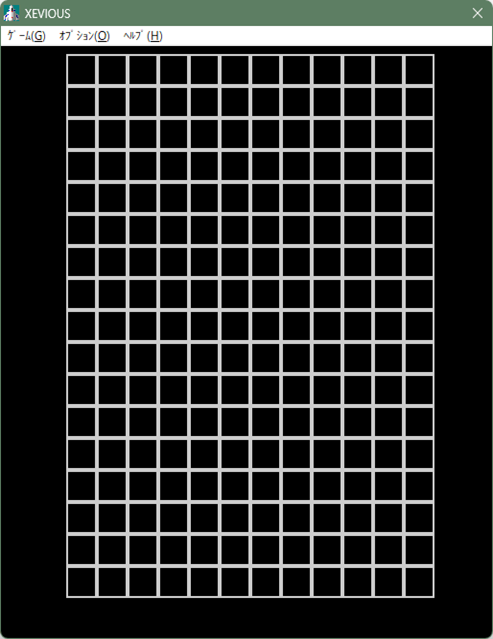

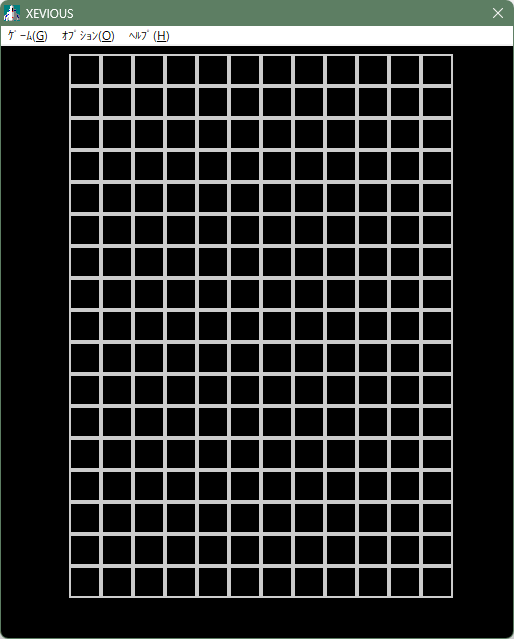

↓Left: image horizontally compressed to 0.96x (equivalent to the

Arcade Archives default). Right: pixel-by-pixel (1:1 pixel

mapping).

Source:『Windows 95/98 version of

Xevious (publisher: MediaKite)』(© Bandai Namco Entertainment

Inc.)

The test grid in Xevious also displays black squares at 14x14

pixels, meaning each square has the same number of pixels

vertically and horizontally.

This strongly suggests that

the developers intended the CRT to be adjusted so that each

pixel appears as a true square.

* On modern PCs

and consoles, this corresponds to a 1:1 pixel-mapping

(pixel-by-pixel) display.

When adjusted this

way, Andor Genesis becomes a perfect square, matching exactly

how we remember it. Its presence — that distinctive look it has

precisely because it is a square — finally returns.

For

players who experienced the game through retro PC ports, this

accuracy can bring back old memories and even change how

enjoyable the game feels after playing.

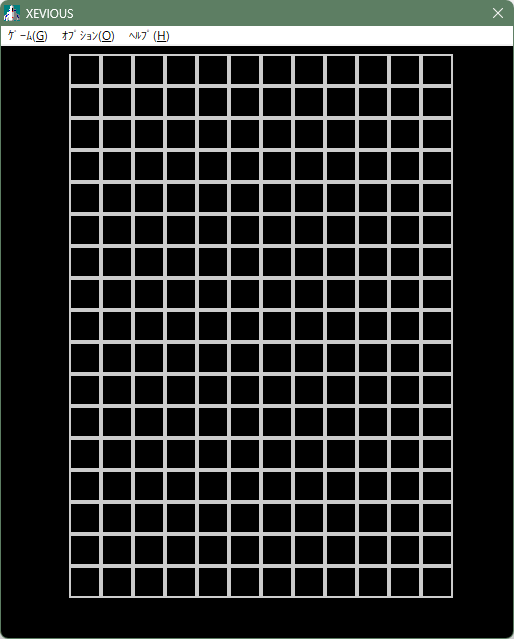

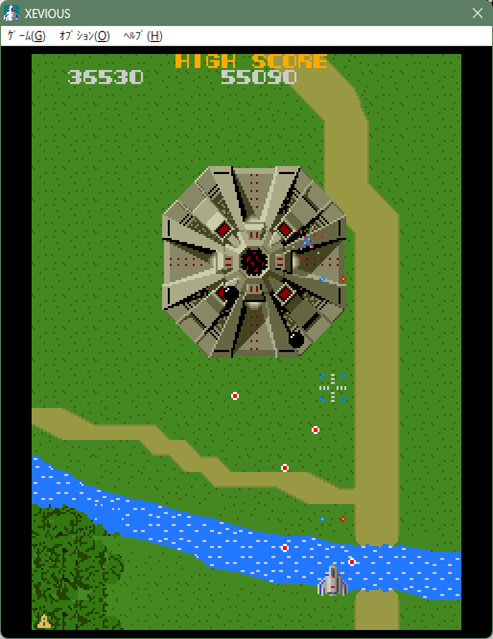

↓Left: image horizontally compressed to 0.96x (equivalent to the

Arcade Archives default). Right: pixel-by-pixel.

Source:『Windows 95/98 version of

Xevious (publisher: MediaKite)』(© Bandai Namco Entertainment

Inc.)

There is another decisive reason why pixel-by-pixel

display is the correct way to view Xevious.

Andor Genesis

was also released as plastic model kits and stickers, and

in every case it is depicted as a perfect square.

By

contrast, earlier ports such as the PC Engine version and the

Famicom version (with a horizontal pixel ratio of 1.14x)

deviated significantly from a true square due to hardware

limitations.

To repeat the point: even if the pixel

aspect ratio is incorrect, Xevious is still an outstanding game

with so much going for it that you can absolutely enjoy it.

However, whether you end up loving the game as deeply

as many fans do can be heavily affected if the pixel aspect

ratio is wrong. That is my personal view.

One possible

reason this 'close enough is fine' mindset has spread is that

the default settings in MAME, the arcade-board emulator, use a

similar aspect-ratio calculation.

Because of that, more

and more recent releases seem to assume that if others are doing

it this way, then it must be acceptable for them as well.

Both the Arcade Archives version and the Origin Collection

version allow you to switch to a pixel-by-pixel display, so it

is not a fatal issue.

However, most players will

naturally start by playing with the default settings.

So, does a correct method for determining the proper

pixel aspect ratio actually exist?

We will explore that in

the next chapter.

|

What should be used as the basis for determining

the correct

pixel aspect ratio

【1】.For games that display a test grid pattern at startup or in

test mode, aligning it to a perfect square is almost always

correct.

The very fact that the game displays a test grid pattern is

essentially the developer’s way of saying, 'Please adjust this

so the squares are perfectly square.'

Back in the day,

arcade operators would look at this white grid pattern and

adjust the aspect ratio accordingly.

* Update

(January 14): I found an article that documents how

these adjustments were actually done in real arcades.

Another Day at Hey, Day 21 Game Culture Preservation Institute

According to it, what I refer to here as the test grid was often

called a 'crosshatch' on site, which also matches how many

arcade PCB manuals described it."

If the test grid

pattern contains square cells with the same number of pixels

vertically and horizontally, it means the developers intended

the game to be displayed pixel-by-pixel.

Therefore, when

such a game is re-released or ported, a pixel-by-pixel display

is the optimal choice. (Examples include the original Gradius,

Gradius II, and Xevious.)

* The only major exception

is Capcom’s CPS hardware (Daimakaimura, Final Fight,

Street Fighter II, etc.).

If you align its test grid

to a perfect square, the characters become noticeably wide, so a

different method of adjustment is required."

Home consoles of the Famicom and PC Engine

era did not output square pixels due to cost constraints.

However, many arcade boards—where higher manufacturing costs

were acceptable—were designed from the beginning to display each

pixel as a true square (pixel-by-pixel).

For games that

do not display a test grid pattern, the pixel aspect ratio must

be determined using the following method.

【2】.Connect the arcade board to a CRT monitor set to its

standard settings, and treat the pixel aspect ratio that appears

without any adjustment as the correct one.

In this context, 'standard settings' refers to a state in which

a CRT monitor displays a television broadcast without any

vertical or horizontal distortion. Most CRT monitors were

shipped in this condition.

If a game does not provide a

test grid pattern, there are no other reliable reference points,

so the pixel aspect ratio seen under these standard settings is

treated as the correct one.

* Capcom’s CPS

hardware (Daimakaimura, Final Fight, Street Fighter II, etc.)

is an exception. When displayed under these standard

settings, all characters appear noticeably thin.

Since this

hardware provides no clear reference for adjustment, the aspect

ratio was likely left entirely to the discretion of arcade

staff.

* Irem’s M72 hardware (R-Type, Ninja Spirit,

etc.) is also an exception.

Under standard settings,

characters likewise appear thin, and because the board offers no

test grid or other reference points, operators probably had to

rely on their own judgment.

For both CPS and M72 boards,

arcade staff may have adjusted the aspect ratio by looking at

round elements on screen—such as the circular dots in the R-Type

title logo—and tuning the image until those shapes appeared

correct.

【3】.Arcade staff would adjust the monitor so

that the image appeared as large as possible while keeping the

aspect ratio intact.

Once the aspect ratio had been determined, arcade staff would

typically enlarge the image as much as possible to make it look

appealing.

However, during this process, slight

variations in aspect ratio often occurred depending on the

operator’s personal judgment.

Some operators may have

ignored the intended aspect ratio altogether and simply

stretched the image to fill something close to a 4:3 television

screen.

In fact, this incorrect approach is

essentially how MAME—the arcade-board emulator—determines its

aspect ratio.

From an implementer’s perspective,

stretching the image all the way to a 4:3 frame can appear

reasonable at first glance.

Because of this, not only

MAME but even early versions of my own emulator, Ootake,

expanded the image too far using this method, and several

emulators still rely on this incorrect approach today.

The reason this full‑screen expansion is not correct is that

many arcade boards include black borders—non‑active

display areas—either at the top and bottom or on the sides.

When the image is stretched to fill these inactive regions,

the intended aspect ratio becomes distorted.

Because some

developers of modern re-releases have used this incorrect method

as their reference, many titles end up being sold with an

inaccurate pixel aspect ratio as the default setting.

【4】.The pixel aspect ratio determined using the method described

in 【2】 can be calculated simply by referring to the arcade

board’s specifications, even without physically connecting the

hardware.

Ideally, developers working on modern re-releases should verify

the results using the method described in 【2】.

However,

the same results can be obtained through calculation without

physically connecting the hardware. In practice, when creating a

port, using these calculated values is likely the most accurate

approach.

In the next section, we will look at the

specific calculations used to determine the correct pixel aspect

ratio.

|

How to Calculate the Correct Pixel Aspect

Ratio

【1】.Calculate the pixel aspect

ratio based on the value defined by ATSC (the Advanced

Television Systems Committee) during the digital transition of

NTSC: the 6.136 MHz pixel clock.

This is the only true reference for pixel aspect ratio in

the CRT era.

It defines that, on a television screen

displaying an undistorted broadcast image, a signal output with

a horizontal frequency of 15.734 kHz, a vertical frequency of

59.94 Hz, and a pixel clock of 6.136 MHz will always produce

square pixels (1:1).

Even before this value was formally

defined, actual measurements suggest that the effective pixel

clock was already very close to 6.136 MHz.

Since the

explanation above may still feel abstract, the following section

describes the actual calculation process.

【2】.What Formula Is Used for the Calculation

Older arcade boards and home consoles were designed to output

video compatible with NTSC CRT televisions, which were

originally intended for broadcasting.

As a result, their

output signals use a horizontal frequency of 15.734 kHz and a

vertical frequency of 59.94 Hz, or values extremely close to

these.

NTSC CRTs have a fixed vertical line count of

262.5 lines in non‑interlaced mode.

Therefore,

the only parameter that varies between different arcade boards

and consoles is the horizontal resolution.

And

the factor that determines this horizontal resolution is

the pixel clock.

The pixel clock can be thought

of as the speed at which the hardware’s drawing cursor

processes pixels—not how fast it moves, but how fast it performs

its work.

A higher pixel clock (a faster rate)

allows the system to draw more finely detailed pixels, resulting

in higher horizontal resolution.

From the pixel clock,

the hardware’s pixel aspect ratio can be calculated immediately.

The calculation is as follows:

6.136 ÷ [the pixel clock of

the arcade board being evaluated]

The result of this calculation is the pixel aspect

ratio.

This value represents how much the hardware’s “one

pixel” is stretched vertically or horizontally compared to the

square pixel defined by ATSC at a 6.136 MHz pixel clock.

・Less than 1.0 → a vertically elongated pixel (narrower width)

・Greater than 1.0 → a horizontally elongated pixel (wider width)

This follows from the fact that a higher (faster)

pixel clock allows more pixels to be packed into a single

scanline, which in turn makes each individual pixel narrower in

width.

The pixel clock values for various arcade boards and game

consoles can be found in the MAME source files or on sites such

as the one below.

Page by Pin Eight (administrator of a

long‑standing video‑technology site active since the early

2000s):

Dot clock rates

Note: “Dot clock” refers to the pixel clock."

When

this method is applied to the PC Engine, the resulting pixel

aspect ratio matches extremely well with the image displayed on

real hardware, as well as with the output of Ootake (Real

Stretched) and Mednafen.

Although Pin Eight’s table is

not a primary source, it compiles values based on real hardware

behavior and the MAME source code.

It also includes

values such as the Famicom’s 8:7 ratio, which many emulators

actually adopt.

Given how few people still publish technical

information today, this resource is genuinely invaluable.

It is also possible to derive the pixel clock from the

precise horizontal frequency and the total horizontal pixel

count (including blanking regions).

In the next section,

we will calculate the pixel aspect ratios for the arcade boards

of the original Gradius, Gradius II, and Xevious.

|

Calculating the Pixel Aspect Ratios of

Gradius, Gradius II, and Xevious

【1】.Calculating "Gradius"

Pixel Aspect Ratio

・Pixel clock: 6.14 MHz

6.136

÷ 6.14 = 0.9993

The pixel aspect ratio is

「0.9993」 (approximately 0.07% narrower than a perfect square

pixel, effectively square)

The result

shows only a 0.07% deviation, which is visually

indistinguishable from a perfect square pixel. In practical

terms, it can be treated as square.

Since the original

Gradius displays a test grid pattern at startup, arcade

operators likely used the adjustment knobs to compensate for

individual CRT variations so that the grid’s squares appeared

correctly proportioned.

Because the black squares in the

test grid are 14×14 pixels (already perfectly square at the

pixel level), a pixel‑by‑pixel (1:1 pixel mapping)

presentation is effectively the recommended approach

when porting the game to modern systems that use square‑pixel

displays, such as contemporary consoles or PCs.

【2】.Calculating "Gradius II" Pixel Aspect Ratio

・Pixel clock: 6.14 MHz (TWIN16 board)

6.136

÷ 6.14 = 0.9993

The pixel aspect ratio is

「0.9993」 (approximately 0.07% narrower than a perfect square

pixel, effectively square)

As a result,

because the pixel clock is identical to that of the original

Gradius, the pixel aspect ratio is exactly the same.

The

test grid pattern is also identical, so a pixel‑by‑pixel

(1:1 pixel mapping) presentation can be considered the

manufacturer‑intended display method.

Gradius II

(320‑pixel horizontal output) expands the horizontal visible

area compared to the original Gradius (256‑pixel horizontal

output). The areas that appeared as black borders on the

left and right in the original Gradius now fall within the

visible region.

The important point here is that

even though the horizontal pixel count (listed as "resolution"

in specification sheets) increases, the aspect ratio of

each individual pixel remains unchanged from the original

Gradius.

Pixel aspect ratio is determined

by the pixel clock, not by the number of

pixels.

【3】.Calculating "Xevious" Pixel Aspect Ratio

・Pixel clock: 6.14 MHz

6.136

÷ 6.14 = 0.9993

The pixel aspect ratio is

「0.9993」 (approximately 0.07% narrower than a perfect square

pixel, effectively square)

As it turns

out, Xevious also uses the same 6.14 MHz pixel clock as Gradius,

so its pixel aspect ratio is identical. The test grid pattern is

likewise the same, meaning that a pixel‑by‑pixel (1:1

pixel mapping) presentation can be considered the

manufacturer‑intended display method.

While many

home consoles did not provide true pixel‑by‑pixel output due to

cost constraints, a large number of arcade boards produced

displays that were much closer to 1:1 pixel mapping.

This

pixel‑accurate output on arcade hardware likely made it

easier for graphic designers of the time to perform their

paint‑based workflow on the high‑end computers used for asset

creation.

That concludes this section. Using the same method, it is also

possible to determine the pixel aspect ratios (PAR) of home

consoles, not just arcade boards.

Next, as noted in the

caution section, let’s calculate the pixel aspect ratios of

Capcom’s CPS hardware and Irem’s M72 hardware.

|

Calculating the Pixel Aspect Ratios of

Daimakaimura and R‑TYPE

【1】.Calculating "Daimakaimura

(Ghouls’n Ghosts)" Pixel Aspect Ratio

・Pixel clock: 8.00 (CPS1 board)

6.136

÷ 8.00 = 0.767

The pixel aspect ratio is

「0.767」 (approximately 23.3% narrower than a perfect square

pixel, resulting in a vertically elongated pixel shape)

As a result, the pixels appear significantly vertically

elongated, being 23.3% narrower than perfect square pixels. With

this uncorrected presentation, many viewers would likely feel

that character sprites look noticeably too thin.

Although

the test mode provides a test grid, aligning it to perfect

squares produces characters that appear excessively wide, which

is clearly incorrect.

In the case of Capcom’s CPS

hardware—an outlier in this regard—it is likely that arcade

operators ultimately relied on visually adjusting the image

by looking at round characters or items on screen,

leaving the final tuning entirely in their hands.

【2】.Calculating "R-TYPE" Pixel Aspect Ratio

・Pixel clock: 8.00 (M72 board)

6.136

÷ 8.00 = 0.767

The pixel aspect ratio is

「0.767」 (approximately 23.3% narrower than a perfect square

pixel, resulting in a vertically elongated pixel shape)

As it turns out, the pixel clock is the same as that of

Daimakaimura, so the pixel aspect ratio is identical. However,

unlike Daimakaimura, this hardware provides no test grid display

at all.

On the CPS hardware used for Daimakaimura, the

presence of a test grid actually led to incorrect adjustments,

but Irem appears to have avoided this issue by omitting

the test grid entirely.

For the M72 hardware as

well, it is likely that arcade operators ultimately relied on

visually adjusting the image by looking at round

characters or items on screen, leaving the

final tuning entirely in their hands.

In R‑TYPE,

the title screen displays “R・TYPE,” with a large round

dot between the R and T. Because this screen alternates

frequently with the demo play sequence, operators could easily

use this dot as a reference to adjust the aspect ratio.

The engineers who developed the CPS and M72 hardware appear

to have prioritized achieving the highest possible

resolution within the constraints of the NTSC standard,

even at the cost of making screen adjustment more difficult.

Because NTSC fixes the vertical resolution at 262.5 lines

including the blanking interval, they pushed the

horizontal resolution as far as practical. Increasing

it any further would have required more expensive CRTs, so it is

reasonable to assume that this led to the choice of a 384‑pixel

horizontal display.

Unlike Namco, Konami, Sega, and

Taito—who tended to keep their pixel aspect ratios close to

1:1—these two companies pursued their own distinctive

graphics specifications. As a result, the pixel art

created for these systems still retains its unique brilliance

today.

|

To Preserve the Appeal of These Classics

for Future Generations

If, during the development of the port, the actual arcade

board had been connected to a CRT monitor for verification, the

default setting would likely not have ended up vertically

stretched.

That said, it is also possible that the

developers thoroughly tested the game and intentionally chose

the vertical stretch for their own reasons. There may have been

circumstances we are not aware of, and therefore it cannot be

criticized outright.

Today’s home consoles and PCs have

more than enough performance to scale images without blurring.

As long as either the vertical or horizontal axis is scaled by

an integer factor, visual artifacts remain minimal.

We

are no longer in an era where "hardware limitations make it

impossible to reproduce the correct aspect ratio."

Most

players experience a game in its default settings.

For

that reason, I strongly hope that the very first screen is

presented in a way that does not diminish the appeal of these

masterpieces.

Through such continued efforts, the appeal

of these classic masterpieces will be conveyed deeply to younger

generations, allowing the works to keep living on for many years

to come — and far beyond.

|

2026.1.3-2026.1.15 Written by Kitao Nakamura.

"Ootake" Homepage へ 戻る

|

Twitter(X)始めました

Twitter(X)始めました